When the Dawson County Sheriff’s Office recently announced the first deputy from the agency to achieve a phlebotomy certification through a new state program, many citizens voiced their concerns.

Dialogue through DCSO’s Feb. 25 Facebook post yielded various questions about what the program is-and what it isn’t. DCN reached out to Dawson County Sheriff Jeff Johnson and the deputy who earned the certification to gain additional insight.

What is the program?

As a refresher, the Governor’s Office of Highway Safety recently started a new grant-funded program which allows law enforcement officers (LEOs) to become certified in phlebotomy practices, according to DCSO’s press release. Georgia is the 13th state to implement a law enforcement phlebotomy program. Arizona was the first state to start such a program in 1995.

Who received the certification?

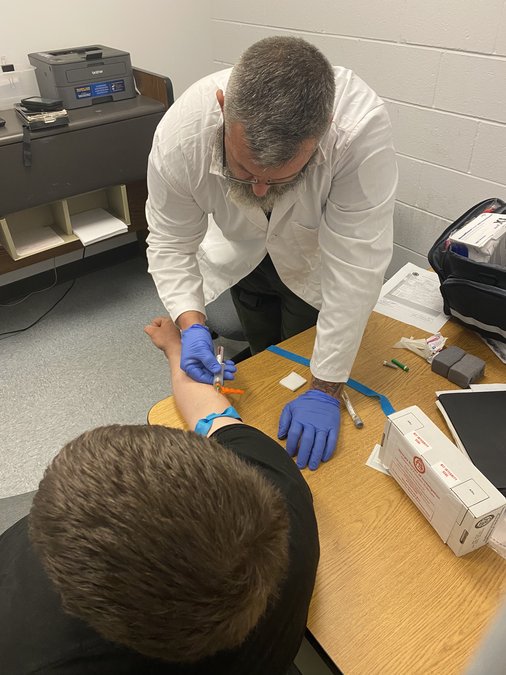

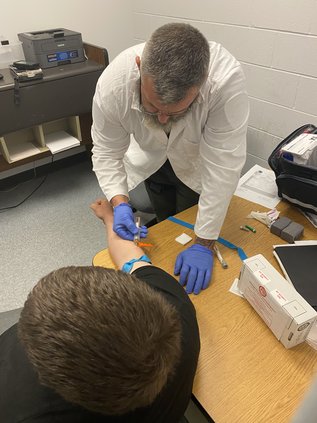

DCSO HEAT Deputy Provost recently graduated from Georgia’s inaugural LEO phlebotomy class along with 15 others from around the state. With this certification, he can now perform blood draws at the Dawson County Detention Center rather than having to transport suspects to other medical care facilities. At the end of February, Provost performed the sheriff office’s very first blood draw on someone suspected of a drug-related DUI.

What training does the deputy have?

Through the program, Provost and his classmates now possess the same set of skills that phlebotomists who work in a variety of medical settings do.

They participated in online and in-person training through West Georgia Technical College. As part of the training, they practiced phlebotomy skills by having people come to their class rather than going out to do clinicals, Provost said during a phone interview.

This helped because of hospitals’ COVID-19 restrictions and the fact that class participants came from agencies all around Georgia, so the technical college provided a central training spot, he added.

Why is this program necessary?

The need for such training starts with agencies’ move away from breathalyzers as a DUI indicator because of accuracy concerns.

“The state has deemed breath tests not really acceptable, so if someone refuses, we can’t use it against them,” said Provost, “so a lot of agencies have started going to blood draws. Breath tests aren't going to show the presence or use of drugs, which is high in Dawson [County].”

With the most recent uptick in COVID-19, EMS and hospitals have again struggled with a surge of patients, often leading to a delay in a blood draw.

That delay has become particularly apparent to officers like Provost. After people suspected of DUIs consent to a blood draw, he usually takes them to the local urgent care clinic. The clinic’s pandemic-related restrictions and closing time of 7 p.m. make it difficult for blood draws to be performed in Dawson County, especially since DUI suspects tend to be spotted later at night.

So, officers would have to drive a suspect to somewhere like Lumpkin County and expose them to a hospital setting, which isn’t ideal, in order to get blood drawn.

People have to be admitted into the E.R. and triaged, so they have to wait for a lab tech who’s in between seeing other patients.

The time delay can also impact blood alcohol content, which decreases by 0.0125-0.015 grams per hour, Johnson said in an email.

Additionally, a lab tech or phlebotomist who takes a DUI suspect’s blood may be subject to a subpoena should a case go to trial. In that circumstance, the medical professional could lose a whole day’s pay, Provost said.

Instead of the DUI arrest process taking three hours from apprehension to blood testing to booking, he elaborated that it only takes about 30 minutes now.

“It gives them (suspects) less time in an uncomfortable position handcuffed in the back of the car, and it takes liability away from DCSO while the person is in the car [for less time],” he added.

Have laws changed?

“The same laws are in place regarding implied consent,” Johnson said. “The only difference is that these specially-trained deputies now have the ability to draw blood, which saves the officers time (travel to and from a medical facility and the time spent waiting), is safer and reduces fuel costs.”

Under Georgia law, law enforcement can only obtain a blood draw of a suspected DUI driver if an individual consents, or a search warrant is obtained, according to DCSO’s Feb. 25 post.

Implied consent for suspects 21 years of age or older means that they are required to submit to blood, breath, urine or other testing if suspected to be under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Refusal of such tests will lead to the suspension of one’s Georgia license or privileges to drive in the state for one year, and that refusal can be used as evidence at trial. If tests show a BAC of .08 grams of more, a person’s license may also be suspended for a minimum of one year.

People are entitled to additional testing at their own expense.

Implied consent for suspects under the age of 21 means that they are required to submit to testing if suspected to be under the influence of alcohol or drugs. The law’s parts about test refusal, that refusal’s usage as evidence and additional test costs are the same as with older suspects. However, suspects younger than 21 may also have their licenses suspended if their tests show a BAC of just .02 grams of more.

Will there be roadside blood draws?

No, said Johnson.

What about blood draws on unconscious people?

The short answer is no, DCSO would not be doing that.

“Unconscious suspects will most certainly be transported to an emergency medical facility where the medical care providers would handle the draw,” Johnson said.

“DCSO would not be doing it as a first concern rather than making sure the person has medical treatment…it would not be the number one priority,” Provost added.

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that police can draw blood evidence when a suspected drunken or drugged driver is unconscious as well, DCSO’s Feb. 25 post stated.

However, Provost said the people who would be most trained to perform this type of draw would be state troopers, not DCSO deputies.

Specific troopers are trained for responding to serious vehicle accidents. And even then, they would only respond and perform a blood draw if a patient had to be transported to an out-of-state medical facility, and blood would be drawn through existing IVs that EMTS/paramedics place.

What’s the future of LEO phlebotomy training?

Johnson reiterated that many states are already utilizing specially-trained law enforcement officers to conduct blood draws. The recent class attended by Dep. Provost included officers from various agencies including the Georgia State Patrol.

“We do expect one other deputy to be trained and certified in order to do so (perform blood draws) in the near future,” Johnson said. “I fully anticipate that you will see more and more agencies taking advantage of this training.”